- The Town Walls of Wexford – History and Archaeology

- What is a Walled Town?

- The Walls

- Wexford before the Walls

- Viking Wexford

- Life in the Viking Settlement

- Life in the medieval walled town

- Economy and Industry of the Medieval Walled Town

- Trade and the Medieval Quays of the Walled Town

- The churches of the walled town

- Defend and Protect

- Conservation Plan

The Town Walls of Wexford – History and Archaeology

Information supplied and compiled by Stafford McLoughlin Archaeology

All text and images are copyright of Stafford McLoughlin Archaeology unless otherwise stated. Please cite this information as; McLoughlin, C. 2013 The Town Walls of Wexford: History & Archaeology. Buildings of Co. Wexford Website.https://buildingsofwexford.com/wexford-town-cultural-spine/town-wall/

What is a Walled Town?

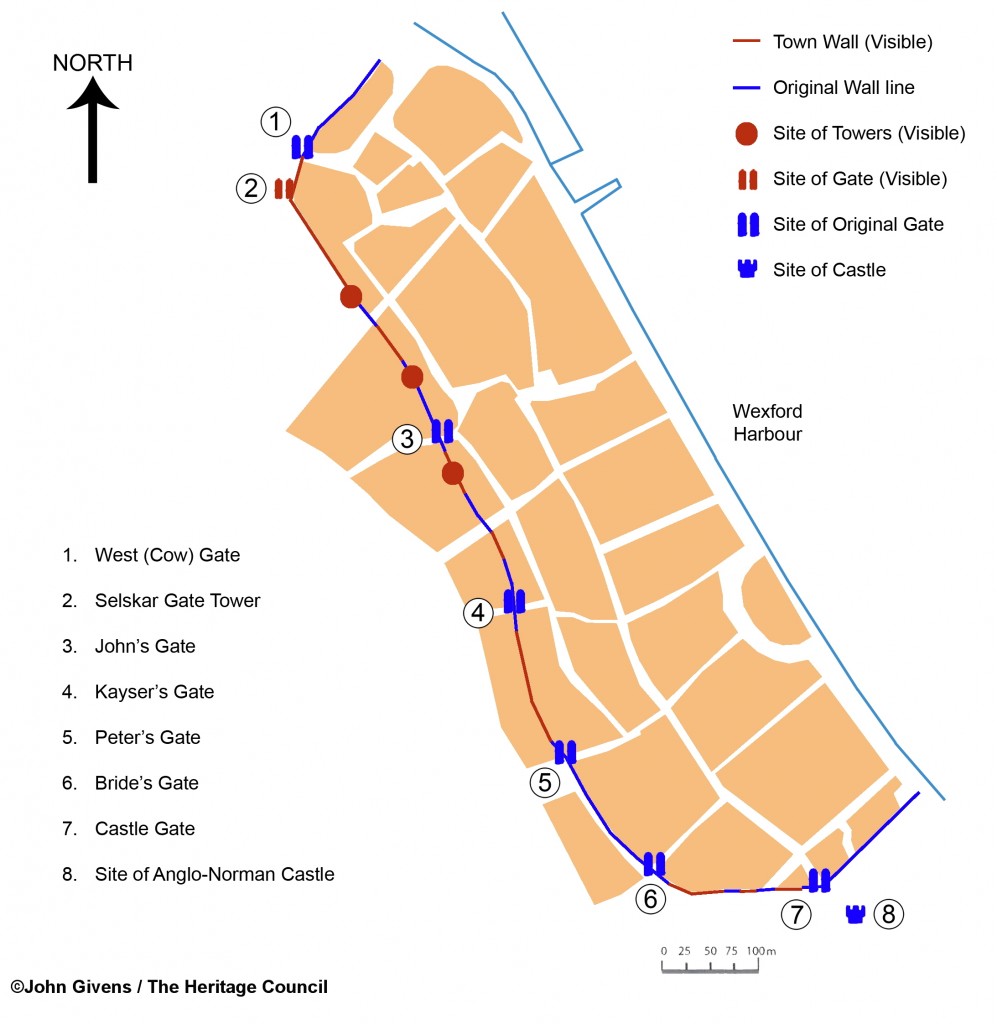

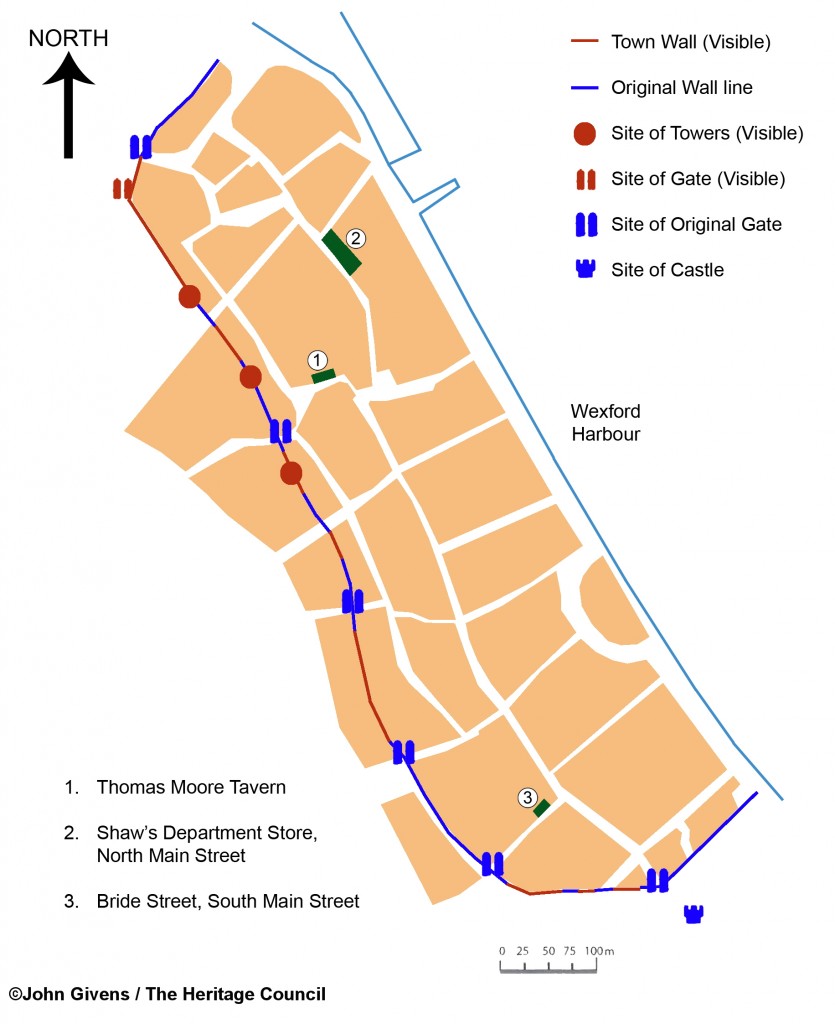

Map showing line of Town Wall

The Town Walls of Wexford – History and ArchaeologyWhat is a Walled Town?Irish Walled Towns were initially the creation of the Anglo-Norman colonists who settled here in the late twelfth century. A town was created, often on the site of an existing settlement, which was then enclosed by a defensive wall. The residents of the town received a set of privileges defined in a charter granted to them by the lord on whose land the town was situated. Some medieval walled towns, like Wexford, were a continuation of defended settlements created by the Viking Norse settlers of the tenth and eleventh centuries.

There are over 50 walled towns in Ireland, all of which are defined by the remains of a wall or other defences which date to between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries. Dublin was one of the earliest towns to be walled, basing its defences on the earlier Norse fortifications, and Bandon, Co. Cork, was one of the latest walled towns, with fortifications dating to the seventeenth century. The presence of a stone wall imparted a strong sense of importance and it was both a defensive feature and a status symbol.

The town walls generally consist of a perimeter wall known as a curtain wall with mural towers and gatehouses placed at intervals in the wall. The towers were defensive in nature as were the gatehouses, which also controlled access to and from the town. In the wealthier towns such as Dublin and Waterford some non-essential mural towers were built which functioned mainly as residences.

The walled towns of Ireland vary in shape and size depending on topographic and economic factors. The largest walled town in Ireland is Kilkenny, whose walls encompass an area of 43 hectares. Wexford occupies an area of 25 hectares. Many of the walled towns are located on major rivers or facing the sea, as water was the primary route for the movement of goods and people during the medieval period.

The creation of walled towns was the direct result of colonisation, and for many of the towns defence was of primary concern. By the middle of the thirteenth century attacks on walled towns were common, either by feuding Anglo-Norman lords or from attacks by the native Irish. However by the eighteenth century many town walls were no longer required and some were actively removed by town corporations, whilst others fell into decay.

The Walls

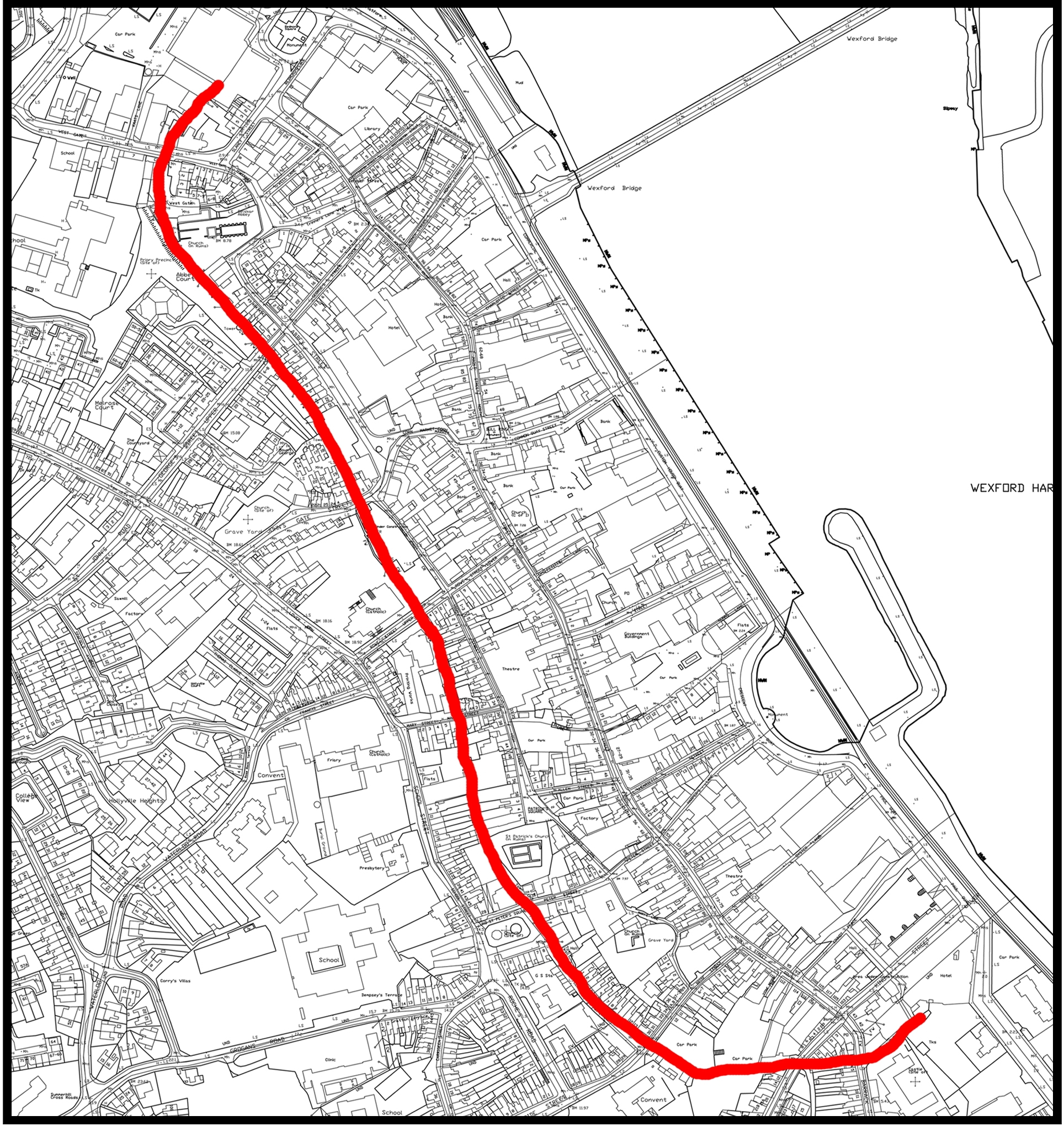

Ordance Survey Map of Wexford Town showing line of town wall

Where can I see Wexford’s town walls?

About two thirds of Wexford’s medieval walls survive in varying states of preservation. They enclosed an area of 25 hectares which formed an elongated strip along the open shoreline of Wexford Harbour and had a total length of 1.2km. Unlike some other walled towns, such as New Ross,Wexford was not walled on the seaward side.

No records survive for early murage grants for the building of Wexford’s walls but it is likely that they were begun shortly after the expulsion of the Norse from the town in the late twelfth century. Traditionally they were thought to have been begun by King John and finished in 1300 by Sir Stephen Devereux. A castle was built at the southern end of the town, outside the town wall. There are no remains of the castle, which was replaced in the eighteenth century by the military barracks which still occupies the site.

At the southern end of the town, the walls were constructed from the harbour’s edge on the southern side of King Street, north across Barrack Street and King Street Lower through the Ropewalk Carpark across Bride Street and Peter Street. The wall then continued to the west of High Street across Mary Street and Rowe Street, and across John’s Gate Street. The wall then passed to the west of Abbey Street, crossing Georges Street Upper across to Selskar Abbey where it continued towards West Gate Street and turned north-east back towards the harbour.

There are three surviving towers located along the length of Wexford’s town walls and historic references remind us that there were others which no longer survive. In addition to these towers there were six defended gates into the town; Cow Gate or West Gate, John’s Gate, Kayser’s Gate, Peter’s Gate, Bride’s Gate and Castle Gate. The well preserved West Gate tower was originally called Selskar Gate and was a private gate into Selskar Abbey rather than a town gate. There is also evidence of three internal or ward gates in the town, and gates leading to the quays.

Publically accessible parts of the wall

The best place to see the town wall is the well-preserved stretch which leads from the restored West Gate Tower (originally Selskar Gate). This stretch of wall is c.190m in length and measures 3-4m in height. It incorporates a circular tower as well as West Gate Tower.

Another good place to view the wall is off Abbey Street, where a section of the wall has been recently conserved. This stretch of wall incorporates a circular tower.

The carpark of Rowe Street Church also contains a surviving stretch of the wall. A square tower is incorporated in this section and this can be better seen from the town’s new library building.

Towards the southern end of the town part of the wall can be seen forming the boundary of St. Patrick’s Church. Further to the south another part of the wall can be seen in two carparks at Bride Street and The Ropewalk.

Wexford before the Walls

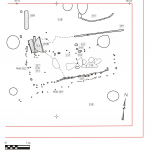

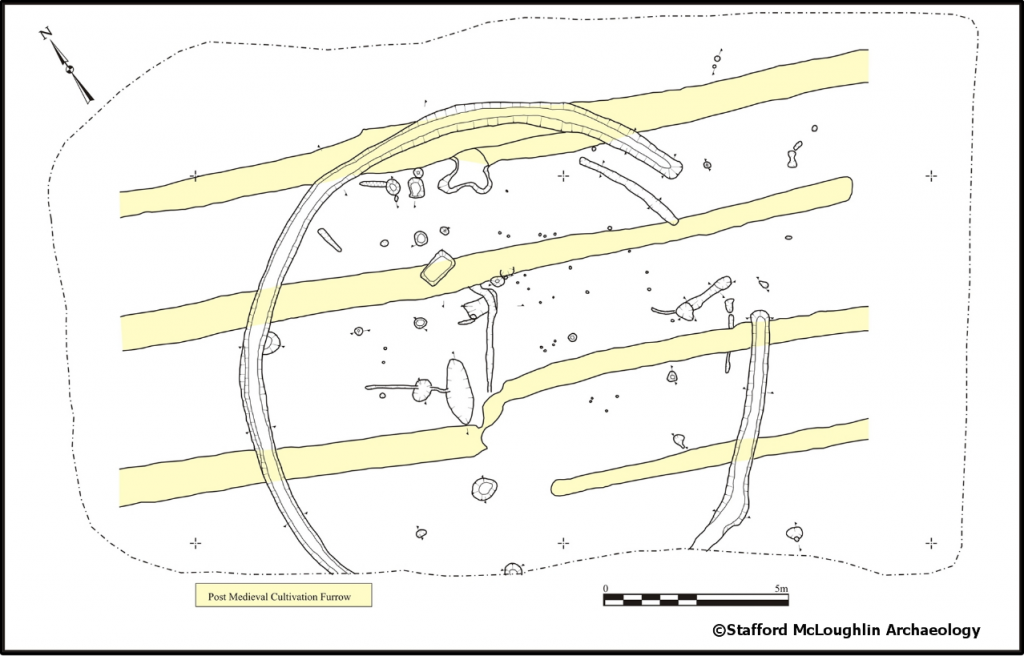

Plan of Iron Age Ring Ditch

What evidence do we have of Wexford before the construction of the town walls?

The town walls and towers which we see today largely date to the medieval and later periods. There is evidence, however, of settlement in the area of Wexford Town prior to the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in the late twelfth century. Prehistoric activity dating to the Neolithic period has been uncovered at a development site in the town, and other prehistoric remains were excavated to the south and north of the town centre. Wexford is however more famously known for its Viking Norse origins and two excavations within the town have revealed evidence of Norse settlement.

Prehistoric Wexford

Evidence of prehistoric activity within the town is sparse; however archaeological excavation during the redevelopment of Whites Hotel in 2003 uncovered a series of stakeholes and pits which had been disturbed by medieval activity. Flint artefacts and a stone axe were recovered from the pits. The artefacts and features suggest that this area of archaeological activity dated to the Neolithic or Stone Age period (c.4500-2500 BC), when Wexford’s shoreline would have been situated in the North Main Street area.

In the townlands of Kerloge and Strandfield, 3km to the south of the town archaeological excavations uncovered the remains of Neolithic pits, Bronze Age ring-ditches (burial features), a habitation structure and burnt mound material, an Iron Age ring-ditch and gullies, and grain-drying pits dating to the Early Christian period. The features uncovered span a date range of 4500 BC to AD 550. The remains were excavated from three separate development sites and show how extensively the area was used during the prehistoric and early historic periods.

In the townlands of Carricklawn and Ballyboggan to the north of the town centre, the remains of several burnt mound sites have been identified. These sites typically date to the Bronze Age (c.2500-500 BC) and are primarily thought of as cooking sites, although it is likely that they had a range of domestic and industrial uses. One of these sites was uncovered beneath the new County Council offices.

At Begerin, which was formerly an island in Wexford Harbour, are the remains of an Early Christian monastic site founded by bishop Ibar in the fifth century AD. Wexford’s coastal location would have been a focus for settlement and ritual activity during all periods in the past.It is likely that further prehistoric and Early Christian period remains await discovery along the shoreline north and south of the town, and indeed within the town itself.

Viking Wexford

Where was the Viking settlement?

The creation of Wexford as a settlement was the work of the Viking Norse who first came to Ireland in the eighth century from Scandinavia. Viking activity in Wexford harbour was first recorded in AD 819 when the monastery at Begerin was attacked. The first mention of a Viking base in Wexford is in 888 when the Annals of the Four Masters record that the Norse ports of Port Lairge (Waterford), Loch Garman (Wexford) and St. Mullins were defeated by the Irish.

The Norse gave the name ‘Waesfiord’, (meaning broad shallow bay) to the area and the settlement which followed was known by the same name. The Norse settlement appears to have been defended although there is currently very little archaeological evidence to let us know what these defences would have looked like.

An Anglo-Norman commentator, named Giraldus Cambrenis, wrote a detailed account of the capture of Wexford from the Ostmen (Norse) and in doing so tells us that the inhabitants of the town, when attacked by the Anglo-Normans, burnt the suburbs and withdrew inside the wall which was protected on the outside by a ditch or moat. Those suburbs appear to have been located in the present day Faythe, a corruption of an Irish word which means ‘a green’.

A bank and ditch were uncovered at Barrack Street in 1995 during the insertion of the town’s main drainage. The bank and ditch, which pre-dated the Anglo-Norman occupation of the town, are likely to be part of Wexford’s earlier defences. If so, it means that the Anglo-Norman walls do not follow the line of the earlier Norse defences, and that the Norse defences may have been small in scale.

The exact extent of the Norse town is not known, although all writers agree that it began at the south somewhere around the Barrack Street area, and extended north to at least Anne Street. Some have speculated that the northern extent of the Norse town was the present-day Cornmarket. However, until evidence is uncovered through archaeological excavation, the size and extent of the settlement is open to conjecture.

Archaeological excavation has, however, shown that Norse settlement was definitely located in the South Main Street area of the town. Two excavations, one at Bride Street and one at 84-86 South Main Street, have produced evidence for Norse settlement. No Norse activity has yet been recorded from the northern half of the town.

Life in the Viking Settlement

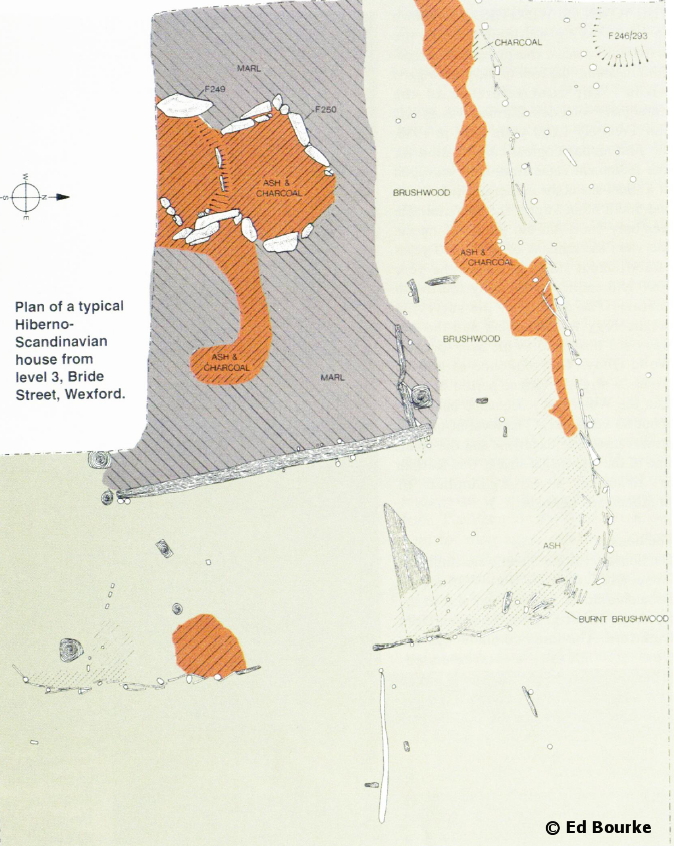

Plan of a typical Viking House excavated at Bride Street

What did archaeological excavation reveal?

Archaeological excavation at two sites in South Main Street revealed the life of the inhabitants of the Norse town. Evidence for houses and industrial activity was uncovered at these sites. To date, these are the only two excavated sites to have uncovered evidence of Norse settlement in the town.

Bride Street

In 1988 excavation was undertaken at a site at Bride Street, close to the junction with South Main Street. The excavation uncovered a series of occupation layers which contained the remains of houses that spanned the early eleventh century to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The earliest house had walls of single post and wattle construction with a clay floor. The succeeding house had walls of sharpened planks driven directly into the earth. None of the earliest houses were aligned with the present day South Main Street. In general the houses were similar to those excavated in Viking Dublin and Waterford. The rectangular houses, which measured on average 7.5m by 6.5m, had hipped thatched roofs supported on four internal roof supports. They had a centre aisle with a centrally placed hearth for cooking on and two side aisles each of which contained a bedding area. The houses would have had a lifespan of 20-30 years before being demolished and replaced.

84-86 South Main Street

This site lies c.50m to the north of the Bride Street site. Archaeological excavation uncovered part of the original shoreline running southeast to northwest across the site. This steeply sloping area was reclaimed at an early stage in the town’s development by the dumping domestic waste to provide a level surface.

Various phases of Norse and twelfth / thirteenth century surfaces, posts, stakeholes, and hearths were uncovered during the excavation. A series of prepared surfaces were laid on what would then have been a shore-side site. The prepared surfaces overlay, and were overlain by, a series of substantial sandy gravel reclamation or storm deposits and thin charcoal activity layers.

In the southern half of the site a substantial stone-lined hearth surrounded by a charcoal rich occupation layer and two large clusters of stakeholes may have represented an industrial area or the inside of a dwelling of which the external walls did not survive. A line of stakeholes represented a structure of at least 3.5m length which enclosed an area to the south and east of the excavation. Interestingly, this structure, which may well have been a dwelling house, was oriented roughly perpendicular to the existing line of South Main Street but extended beyond the site’s existing street frontage.

Life in the medieval walled town

Map of Wexford Town showing the Medieval house sites

Following the takeover of the town by the Anglo-Normans in the late twelfth century, the town was walled and extended and granted borough or town status. This attracted colonists from Britain called burgesses, who were granted plots of land on which to build houses and conduct business. Privileges of town living included liberty of movement, freedom from certain taxes and the right to self-administration. The lord or town founder received rent from the burgesses, as well as other revenues such as court fines and tolls.

Evidence of medieval house remains, dating from the late twelfth century to the thirteenth century, have been uncovered at three locations throughout the town and areas of medieval activity and associated settlement have been uncovered at many others. The house sites were located at the Thomas Moore Tavern in Cornmarket, at Shaw’s Department Store on North Main Street, as well as at Bride Street.

Thomas Moore Tavern

Archaeological excavation during the re-development of the Thomas Moore Tavern revealed the remains of a structure 2.6m below the present ground level which consisted of a series of post and wattle walls, a west facing doorway, a stone-lined hearth and some internal partitions. As uncovered, the remains of the house measured 3.85m east to west by 3.65m north to south. An extrapolation based on the position of the doorway and hearth suggests a total internal width of 5.4m and a possible internal length of 6m or more.

The west facing doorway consisted of the bases of two upright squared timbers which functioned as doorjambs and a horizontal plank threshold. The hearth was defined by a series of 8 stones set on their thin edges and the clay base of the hearth was fire-reddened and charcoal flecked.

Shaw’s Department Store

Archaeological excavation prior to the construction of Shaw’s Department Store, on North Main Street, uncovered a series of flood and occupation debris which indicated that by the late twelfth or thirteenth century land reclamation had allowed for settlement on the eastern side of North Main Street. Post and wattle fences aligned east-west indicated riverside plots and by the mid thirteenth century a stone built house was constructed with internal divisions, a paved interior and hearth sites of both a domestic and industrial nature.

Bride Street

The Bride Street medieval houses were a continuation of the Norse occupation of the same site.

Economy and Industry of the Medieval Walled Town

Several of the sites excavated in medieval Wexford had conditions favourable for the preservation of wooden and leather artefacts and animal bone. Soil samples taken from the sites also revealed the diet of the inhabitants and excavated features such as wells and rubbish pits can tell us of the economy and industry of the townspeople.

The medieval burgesses or townspeople were given a plot of land to live on called a burgage plot. This generally consisted of a long narrow strip with street frontage on which to build a house. Excavation has shown that the area to the rear of the street front was generally full of rubbish pits filled with domestic debris such as pottery, leather artefacts and animal bones. Excavation at White’s Hotel revealed several burgage plots separated by narrow gullies and excavation at 113 North Main Street revealed many medieval pits filled with pottery and animal bone.

Soil samples taken from the fill of pits at Bride Street show that oats, barley, apple, hazelnuts, sloe, bilberry and figs were all eaten by the inhabitants. A great variety of fish was eaten including cod, ling, hake, whiting and gurnard, and cattle, sheep and pigs were the main domestic animals eaten. The range of skeletal elements of the animals present shows that butchering was taking place in the backyards of the houses.

The remains of oak barrel lids or bases, as well as three staves from an open cylindrical vessel were recovered from the medieval house at the Thomas Moore Tavern. The soles of medieval leather shoes were also found here.

At the site of the Theatre Royal evidence of medieval quarrying was uncovered, as well as many medieval rubbish pits. The quarried rock was probably used for the construction or repair of the town wall, or the building of the town’s stone dwellings and castles.

Wells have been uncovered at several of the sites excavated within the walled town. These stone lined features, some of which were entered by climbing down steps, would have been a common feature of the medieval and later town as the principal means of procuring fresh water.

The material uncovered from the excavations shows that a variety of economic processes such as coopering and tanning were going on within or close to the medieval town. As yet no medieval tanneries have been uncovered in Wexford but they were very common in the post-medieval period. The animals and foodstuff required to feed the populace of the towns were probably reared and grown in the town’s agricultural hinterland and brought to the town market for sale. A pig farrowing pen excavated at Bride Street indicates that at least some small-scale animal husbandry was also taking place within the town itself.

Trade and the Medieval Quays of the Walled Town

Medieval silver coin from excavations at White’s Hotel

Wexford was first founded as a trading settlement by the Viking Norse. When they arrived sometime in the ninth or tenth century the coastline looked very different. Wexford Harbour at that time was a reed-fringed wilderness. Archaeological excavations have shown that extensive sea-front reclamation was begun by the Anglo-Normans in the late twelfth century. The reclamation was intended to improve the shipping capabilities of the town as water was the principal transport method of the time.

When the Norse first landed in Wexford the area now occupied by South and North Main Streets would have been foreshore. Evidence of the original shoreline was uncovered at a site around 84-86 South Main Street, 4m inland of South Main Street. At North Main Street the marshy seafront area extended in as far as the middle of the site now occupied by White’s Hotel.

When the Anglo-Normans arrived they set about extending the town, both to the north and to the east. The continual process of land reclamation is a possible reason why Wexford was never walled on the seaward side like so many other Irish port towns.

Archaeological investigations at a large development site at Paul Quay uncovered a phase of the development of the medieval quays. Stone built walls, one of them 1.6m wide, along with organic deposits and medieval pottery, were uncovered to the east of South Main Street. Deposits to the seaward side of the walls contained post-medieval artefacts indicating that the medieval quays were active in this part of the town until the seventeenth century when new jetties and quays were constructed further out in the harbour waters.

During the medieval period the quays would have been a continual focus of activity of the town with ships coming and going on a daily basis. As well as fishing boats, ships would have been coming to port with goods for sale. One of the most interesting ways in which we see how trade was being conducted is from the evidence of imported pottery. Pottery recovered from several archaeological excavations shows that the majority of that which was used in medieval Wexford, was of local Irish origin. However a significant proportion of the recovered pottery was imported from England, as well as France, Iberia and the Low Countries.

Wine was widely traded across medieval Europe and into Wexford Town, as was corn, wool and hides. Of most significance though, Wexford was known as a fishing port, and was Ireland’s leading fishing port in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. The oyster beds in Wexford Harbour made a significant contribution to the towns past economic prosperity and the large volumes of oysters once consumed in the town are remembered in the placename ‘Oyster Lane’.

The churches of the walled town

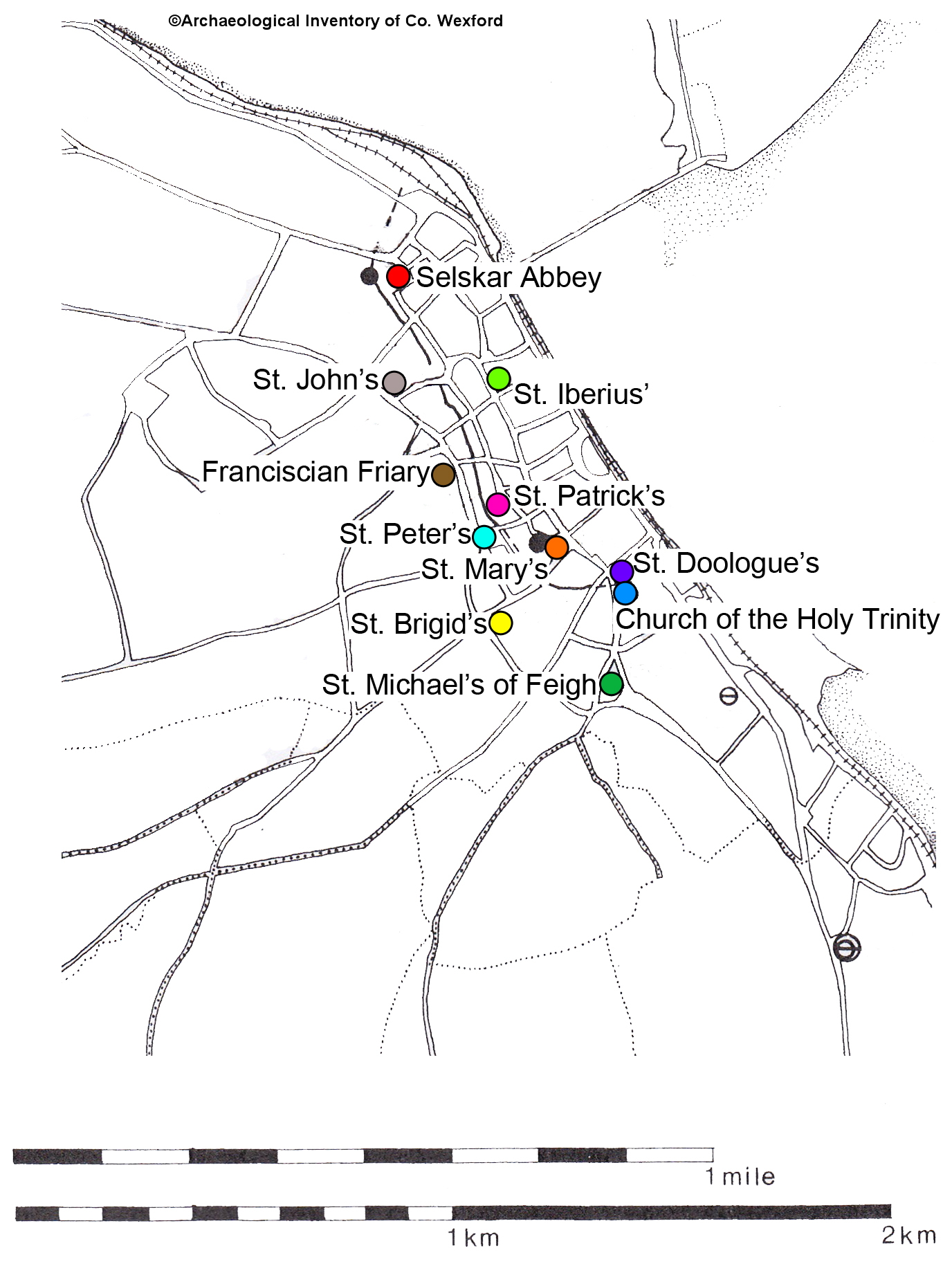

Location of the churches of the walled town

There were five churches within the walled town of Wexford as well as six churches outside the walls. This complex system of churches and parishes was the result of Anglo-Norman additions to the network of churches already built by the Norse. The large number of churches in Wexford contrasts sharply with other Anglo-Norman towns, which were generally based on just one parish.

Norse Wexford contained the parishes of St. Doologue’s, St. Mary’s, and St. Patrick’s, whilst just outside the town were the churches of the Holy Trinity, St. Michael’s, St. Bridgid’s and St. Peter’s. Similar church dedications can be found in the other Norse towns. Dublin for example has dedications to St. Brigit, St. Michael, St. Patrick, St.Olave (Doologue), St. Mary and the Church of the Holy Trinity.

Following the 12th century arrival of the Anglo-Normans, more churches were founded in Wexford; St. Selskar’s, St. Iberius’, St. John’s, and the Franciscan friary.

Of these eleven church sites, ruins of medieval churches or graveyards can be seen at St. Patrick’s, St. Mary’s, St. John’s, St. Michael’s of Feigh, and Selskar Abbey. St. Iberius’ Church and the present Franciscan friary church are reputed to stand on the sites of earlier buildings. The exact location of St. Doologue’s and the Holy Trinity are unknown and there are no visible remains of the churches of St. Peter’s and St. Bridgid’s.

The remains of St. Patrick’s Church consist of a double nave and a chancel. The earliest part of the church dates to the twelfth or thirteenth century. An arcade of four arches which once featured plank centering separates the naves. There is a double bell-cote over the western gable and another over the chancel arch at the east. J.B.Cullen, writing in 1895, tells us that ‘Two eyelitbelfries, set east and west respectively, are a peculiar feature of St. Patrick’s. One of these, which stood above the altar, contained the ‘Sanctus Bell’ which was rung from the sanctuary at the more solemn parts of service’.

St. Mary’s Church was a double nave church similar to St. Patrick’s. References to the church date from 1365. The present remains consist of the western gable of one aisle, which is located within a large graveyard.

Abbey is thought to have been founded by the Roche family as a priory for the Augustinians and was in existence by 1240, dedicated to SS Peter and Paul. The surviving remains consist of a double-nave church, of probable thirteenth century date, with an arcade of four pointed arches separating the aisles. A well-preserved fortified tower is situated at the eastern end of the nave. The abbey is located within an extensive graveyard.

St. John’s

The parish church of St. John was founded early in the thirteenth century. No traces of the church remain. There is an upstanding medieval sarcophagus in the graveyard which acts as a gravemarker.

St. Michael’s of Feigh

There are no visible remains of the parish church of St. Michael’s which was located in the Norse suburbs. The church was in ruins by 1680 but the graveyard still remains

Defend and Protect

The first Wexford town wall was built by the Danes sometime after the town was founded, in about 850 AD.